What Method Of Assimilation Did Settlers Use To Target Native American Youths?

| | This article is missing data nearly cultural genocide of Native Americans in Canada. (May 2021) |

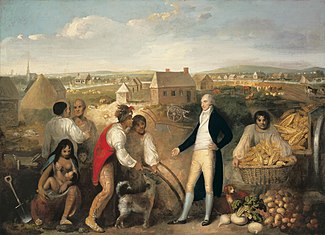

The cultural assimilation of Native Americans refers to a serial of efforts by the U.s.a. to digest Native Americans into mainstream European–American culture between the years of 1790 and 1920.[1] [2] George Washington and Henry Knox were kickoff to propose, in the American context, the cultural absorption of Native Americans.[three] They formulated a policy to encourage the so-called "civilizing process".[ii] With increased waves of immigration from Europe, in that location was growing public support for educational activity to encourage a standard prepare of cultural values and practices to be held in common by the majority of citizens. Instruction was viewed as the master method in the acculturation process for minorities.

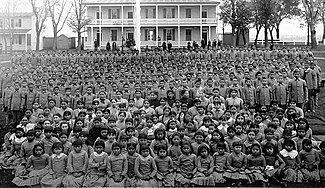

Americanization policies were based on the idea that when ethnic people learned customs and values of the The states, they would be able to merge tribal traditions with American culture and peacefully join the majority of the guild. Afterward the end of the Indian Wars, in the tardily 19th and early 20th centuries, the federal government outlawed the practice of traditional religious ceremonies. It established Native American boarding schools which children were required to attend. In these schools they were forced to speak English, study standard subjects, attend church, and leave tribal traditions behind.

The Dawes Act of 1887, which allotted tribal lands in severalty to individuals, was seen every bit a manner to create individual homesteads for Native Americans. Land allotments were made in exchange for Native Americans becoming US citizens and giving up some forms of tribal self-government and institutions. It resulted in the transfer of an estimated total of 93 1000000 acres (380,000 km2) from Native American command. Well-nigh was sold to individuals or given out gratis through the Homestead police, or given directly to Indians as individuals. The Indian Citizenship Act of 1924 was also part of Americanization policy; it gave full citizenship to all Indians living on reservations. The leading opponent of forced assimilation was John Collier, who directed the federal Function of Indian Diplomacy from 1933 to 1945, and tried to reverse many of the established policies.

Europeans and Native Americans in North America, 1601–1776 [edit]

Eastern Due north America; the 1763 "Proclamation line" is the border between the red and the pinkish areas.

Epidemiological and archeological work has established the effects of increased immigration of children accompanying families from Central Africa to North America between 1634 and 1640. They came from areas where smallpox was endemic in Europea, and passed on the disease to ethnic people. Tribes such every bit the Huron-Wendat and others in the Northeast particularly suffered devastating epidemics after 1634.[4]

During this flow European powers fought to acquire cultural and economic control of North America, just as they were doing in Europe. At the same fourth dimension, indigenous peoples competed for authorisation in the European fur trade and hunting areas. The European colonial powers sought to hire Native American tribes equally auxiliary forces in their Due north American armies, otherwise composed mostly of colonial militia in the early conflicts. In many cases ethnic warriors formed the peachy majority of fighting forces, which deepened some of their rivalries. To secure the assist of the tribes, the Europeans offered goods and signed treaties. The treaties usually promised that the European power would award the tribe's traditional lands and independence. In addition, the indigenous peoples formed alliances for their own reasons, wanting to go along allies in the fur and gun trades, positioning European allies against their traditional enemies among other tribes, etc. Many Native American tribes took part in King William'south War (1689–1697), Queen Anne's War (1702–1713) (State of war of the Spanish Succession), Dummer'due south War (c. 1721–1725), and the French and Indian War (1754–1763) (Seven Years' War).

As the dominant ability after the Seven Years' War, Smashing United kingdom instituted the Royal Proclamation of 1763, to try to protect indigenous peoples' territory from colonial encroachment of peoples from eastward of the Appalachian Mountains. The document divers a boundary to demacarte Native American territory from that of the European-American settlers. Despite the intentions of the Crown, the announcement did not finer preclude colonists from continuing to migrate west. The British did not have sufficient forces to patrol the edge and keep out migrating colonists. From the perspective of the colonists, the declaration served as one of the Intolerable Acts and one of the 27 colonial grievances that would lead to the American Revolution and eventual independence from Britain.[five]

The United States and Native Americans, 1776–1860 [edit]

The most important facet of the foreign policy of the newly independent United States was primarily concerned with devising a policy to deal with the various Native American tribes it bordered. To this end, they largely connected the practises that had been adopted since colonial times by settlers and European governments.[6] They realized that good relations with bordering tribes were important for political and trading reasons, but they also reserved the correct to abandon these proficient relations to conquer and blot the lands of their enemies and allies alike as the American frontier moved west. The United States continued the employ of Native Americans as allies, including during the American Revolutionary War and the War of 1812. Equally relations with Britain and Spain normalized during the early 19th century, the need for such friendly relations ended. Information technology was no longer necessary to "woo" the tribes to forestall the other powers from allying with them confronting the Usa. At present, instead of a buffer against European powers, the tribes often became viewed equally an obstacle in the expansion of the United States.[5]

George Washington formulated a policy to encourage the "civilizing" process.[2] He had a six-point programme for civilisation which included:

- impartial justice toward Native Americans

- regulated buying of Native American lands

- promotion of commerce

- promotion of experiments to civilize or meliorate Native American society

- presidential authority to give presents

- punishing those who violated Native American rights.[7]

Robert Remini, a historian, wrote that "once the Indians adopted the exercise of private property, built homes, farmed, educated their children, and embraced Christianity, these Native Americans would win acceptance from white Americans".[8] The United States appointed agents, like Benjamin Hawkins, to alive among the Native Americans and to teach them how to live like whites.[3]

How different would be the awareness of a philosophic mind to reflect that instead of exterminating a function of the man race by our modes of population that we had persevered through all difficulties and at last had imparted our Cognition of cultivating and the arts, to the Aboriginals of the Country by which the source of hereafter life and happiness had been preserved and extended. But it has been conceived to be impracticable to civilize the Indians of N America – This opinion is probably more user-friendly than simply.

—Henry Knox to George Washington, 1790s.[7]

Indian removal [edit]

The Indian Removal Act of 1830 characterized the U.S. authorities policy of Indian removal, which called for the forced relocation of Native American tribes living e of the Mississippi River to lands w of the river. While it did not authorize the forced removal of the indigenous tribes, it authorized the President to negotiate land commutation treaties with tribes located in lands of the United States. The Intercourse Law of 1834 prohibited United States citizens from entering tribal lands granted by such treaties without permission, though it was frequently ignored.

On September 27, 1830, the Choctaws signed Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek and the start Native American tribe was to be voluntarily removed. The agreement represented one of the largest transfers of land that was signed between the U.S. Authorities and Native Americans without being instigated by warfare. By the treaty, the Choctaws signed abroad their remaining traditional homelands, opening them up for American settlement in Mississippi Territory.

While the Indian Removal Human action fabricated the relocation of the tribes voluntary, it was often abused by authorities officials. The best-known example is the Treaty of New Echota. It was negotiated and signed by a small fraction of Cherokee tribal members, not the tribal leadership, on December 29, 1835. While tribal leaders objected to Washington, DC and the treaty was revised in 1836, the state of Georgia proceeded to human action against the Cherokee tribe. The tribe was forced to relocate in 1838.[nine] An estimated four,000 Cherokees died in the march, now known as the Trail of Tears.

In the decades that followed, white settlers encroached even into the western lands set aside for Native Americans. American settlers eventually made homesteads from declension to declension, but every bit the Native Americans had before them. No tribe was untouched by the influence of white traders, farmers, and soldiers.

Office of Indian Affairs [edit]

The Office of Indian Affairs (Bureau of Indian Affairs as of 1947) was established on March 11, 1824, as an part of the Usa Department of War, an indication of the state of relations with the Indians. It became responsible for negotiating treaties and enforcing conditions, at least for Native Americans. In 1849 the agency was transferred to the Department of the Interior every bit so many of its responsibilities were related to the holding and disposition of large country assets.

In 1854 Commissioner George W. Manypenny called for a new code of regulations. He noted that there was no identify in the W where the Indians could be placed with a reasonable hope that they might escape disharmonize with white settlers. He also called for the Intercourse Police of 1834 to be revised, as its provisions had been aimed at individual intruders on Indian territory rather than at organized expeditions.

In 1858 the succeeding Commissioner, Charles Mix, noted that the repeated removal of tribes had prevented them from acquiring a gustation for European way of life. In 1862 Secretary of the Interior Caleb B. Smith questioned the wisdom of treating tribes as quasi-independent nations.[6] Given the difficulties of the government in what it considered good efforts to back up separate status for Native Americans, appointees and officials began to consider a policy of Americanization instead.

Americanization and absorption (1857–1920) [edit]

Portrait of Marsdin, not-native homo, and group of students from the Alaska region

The motility to reform Indian administration and assimilate Indians as citizens originated in the pleas of people who lived in close association with the natives and were shocked by the fraudulent and indifferent management of their diplomacy. They called themselves "Friends of the Indian" and lobbied officials on their behalf. Gradually the call for modify was taken up by Eastern reformers.[6] Typically the reformers were Protestants from well organized denominations who considered assimilation necessary to the Christianizing of the Indians; Catholics were likewise involved. The 19th century was a time of major efforts in evangelizing missionary expeditions to all non-Christian people. In 1865 the government began to make contracts with diverse missionary societies to operate Indian schools for instruction citizenship, English, and agricultural and mechanical arts.[10]

Grant's "Peace Policy" [edit]

In his Country of the Union Address on December four, 1871, Ulysses Grant stated that "the policy pursued toward the Indians has resulted favorably ... many tribes of Indians have been induced to settle upon reservations, to cultivate the soil, to perform productive labor of various kinds, and to partially accept civilization. They are beingness cared for in such a way, it is hoped, as to induce those withal pursuing their old habits of life to embrace the only opportunity which is left them to avoid extermination."[xi] The emphasis became using noncombatant workers (not soldiers) to deal with reservation life, especially Protestant and Catholic organizations. The Quakers had promoted the peace policy in the expectation that applying Christian principles to Indian diplomacy would eliminate corruption and speed absorption. Most Indians joined churches but in that location were unexpected problems, such every bit rivalry between Protestants and Catholics for control of specific reservations in club to maximize the number of souls converted.[12]

The Quakers were motivated by high ideals, played down the role of conversion, and worked well with the Indians. They had been highly organized and motivated past the anti-slavery crusade, and after the Civil State of war expanded their energies to include both ex-slaves and the western tribes. They had Grant's ear and became the chief instruments for his peace policy. During 1869–1885, they served equally appointed agents on numerous reservations and superintendencies in a mission centered on moral uplift and transmission grooming. Their ultimate goal of acculturating the Indians to American culture was not reached because of frontier land hunger and Congressional patronage politics.[13]

Many other denominations volunteered to help. In 1871, John H. Stout, sponsored by the Dutch Reformed Church, was sent to the Pima reservation in Arizona to implement the policy. However Congress, the church, and private charities spent less coin than was needed; the local whites strongly disliked the Indians; the Pima balked at removal; and Stout was frustrated at every turn.[xiv]

In Arizona and New Mexico, the Navajo were resettled on reservations and grew rapidly in numbers. The Peace Policy began in 1870 when the Presbyterians took over the reservations. They were frustrated because they did not empathise the Navajo. Nonetheless, the Navajo not just gave up raiding just soon became successful at sheep ranching.[15]

The peace policy did not fully apply to the Indian tribes that had supported the Confederacy. They lost much of their state as the U.s.a. began to confiscate the western portions of the Indian Territory and began to resettle the Indians in that location on smaller reservations.[16]

Reaction to the massacre of Lt. Col. George Custer's unit at the Battle of the Fiddling Large Horn in 1876 was daze and dismay at the failure of the Peace Policy. The Indian appropriations measure of August 1876 marked the end of Grant's Peace Policy. The Sioux were given the selection of either selling their lands in the Black Hills for cash or not receiving regime gifts of food and other supplies.[17]

Code of Indian Offenses [edit]

In 1882, Interior Secretary Henry M. Teller called attention to the "cracking hindrance" of Indian customs to the progress of assimilation. The resultant "Code of Indian Offenses" in 1883 outlined the procedure for suppressing "evil exercise."

A Court of Indian Offenses, consisting of three Indians appointed past the Indian Agent, was to be established at each Indian agency. The Court would serve as judges to punish offenders. Outlawed behavior included participation in traditional dances and feasts, polygamy, reciprocal gift giving and funeral practices, and intoxication or sale of liquor. As well prohibited were "medicine men" who "use any of the arts of the conjurer to prevent the Indians from abandoning their heathenish rites and customs." The penalties prescribed for violations ranged from 10 to ninety days imprisonment and loss of government-provided rations for up to 30 days.[eighteen]

The Five Civilized Tribes were exempt from the Code which remained in event until 1933.[19]

In implementation on reservations past Indian judges, the Courtroom of Indian Offenses became mostly an institution to punish minor crimes. The 1890 written report of the Secretarial assistant of the Interior lists the activities of the Court on several reservations and evidently no Indian was prosecuted for dances or "heathenish ceremonies."[20] Significantly, 1890 was the year of the Ghost Trip the light fantastic toe, ending with the Wounded Knee Massacre.

The part of the Supreme Court in assimilation [edit]

In 1857, Principal Justice Roger B. Taney expressed that since Native Americans were "free and independent people" that they could become U.S. citizens.[21] Taney asserted that Native Americans could be naturalized and join the "political community" of the U.s.a..[21]

[Native Americans], without doubt, like the subjects of any other foreign Regime, be naturalized by the dominance of Congress, and go citizens of a State, and of the The states; and if an individual should leave his nation or tribe, and accept up his dwelling among the white population, he would be entitled to all the rights and privileges which would belong to an emigrant from any other foreign people.

—Primary Justice Roger B. Taney, 1857, What was Taney thinking? American Indian Citizenship in the era of Dred Scott, Frederick Due east. Hoxie, April 2007.[21]

The political ideas during the time of absorption policy are known by many Indians as the progressive era, but more than unremarkably known as the assimilation era[22]) The progressive era was characterized by a resolve to emphasize the importance of dignity and independence in the modern industrialized world.[23] This idea is applied to Native Americans in a quote from Indian Affairs Commissioner John Oberly: "[The Native American] must be imbued with the exalting egotism of American civilization so that he will say 'I' instead of 'We', and 'This is mine' instead of 'This is ours'."[24] Progressives likewise had religion in the knowledge of experts.[23] This was a dangerous idea to accept when an emerging science was concerned with ranking races based on moral capabilities and intelligence.[25] Indeed, the idea of an inferior Indian race fabricated it into the courts. The progressive era thinkers too wanted to expect beyond legal definitions of equality to create a realistic concept of fairness. Such a concept was thought to include a reasonable income, decent working weather, too every bit health and leisure for every American.[23] These ideas can be seen in the decisions of the Supreme Courtroom during the assimilation era.

Cases such as Lone Wolf v. Hitchcock, Talton v. Mayes, Winters v. United States, United States 5. Winans, Usa v. Nice, and United States v. Sandoval provide splendid examples of the implementation of the paternal view of Native Americans every bit they refer back to the thought of Indians as "wards of the nation".[26] Another issues that came into play were the hunting and line-fishing rights of the natives, especially when land beyond theirs affected their own practices, whether or not Constitutional rights necessarily practical to Indians, and whether tribal governments had the power to constitute their own laws. As new legislation tried to force the American Indians into becoming just Americans, the Supreme Court provided these critical decisions. Native American nations were labeled "domestic dependent nations" by Marshall in Cherokee Nation v. Georgia, 1 of the start landmark cases involving Indians.[27] Some decisions focused more than on the dependency of the tribes, while others preserved tribal sovereignty, while nevertheless others sometimes managed to do both.

Decisions focusing on dependence [edit]

United states vs. Kagama [edit]

The United States Supreme Court case United states of america v. Kagama (1886) ready the phase for the courtroom to make even more powerful decisions based on plenary power. To summarize congressional plenary power, the court stated:

The power of the general government over these remnants of a race once powerful, at present weak and macerated in numbers, is necessary to their protection, every bit well as to the safety of those amid whom they dwell. It must exist in that government, because it never has existed anywhere else; considering the theater of its exercise is inside the geographical limits of the United [118 U.S. 375, 385] States; because it has never been denied; and because it alone can enforce its laws on all the tribes.[28]

The determination in United states of america v. Kagama led to the new idea that "protection" of Native Americans could justify intrusion into intratribal diplomacy. The Supreme Court and Congress were given unlimited authorization with which to force assimilation and acculturation of Native Americans into American society.[24]

United States v. Nice [edit]

During the years leading up to passage of the Eighteenth Amendment and the Volstead Deed, United States 5. Nice (1916), was a consequence of the idea of barring American Indians from the sale of liquor. The United States Supreme Court case overruled a conclusion made eleven years before, Matter of Heff, 197 U.S. 48 (1905), which allowed American Indian U.S. citizens to drink liquor.[29] The quick reversal shows how constabulary apropos American Indians often shifted with the irresolute governmental and popular views of American Indian tribes.[xxx] The United states of america Congress connected to prohibit the sale of liquor to American Indians. While many tribal governments had long prohibited the sale of booze on their reservations, the ruling implied that American Indian nations could non be entirely independent, and needed a guardian for protection.

United States 5. Sandoval [edit]

Like United States v. Dainty, the U.s. Supreme Courtroom instance of United States v. Sandoval (1913) rose from efforts to bar American Indians from the auction of liquor. As American Indians were granted citizenship, there was an effort to retain the power to protect them as a group which was distinct from regular citizens. The Sandoval Act reversed the U.Southward. v. Joseph determination of 1876, which claimed that the Pueblo were not considered federal Indians. The 1913 ruling claimed that the Pueblo were "not across the range of congressional power under the Constitution".[31] This case resulted in Congress standing to prohibit the sale of liquor to American Indians. The ruling continued to suggest that American Indians needed protection.

Decisions focusing on sovereignty [edit]

In that location were several The states Supreme Court cases during the assimilation era that focused on the sovereignty of American Indian nations. These cases were extremely important in setting precedents for later cases and for legislation dealing with the sovereignty of American Indian nations.

Ex parte Crow Dog (1883) [edit]

Ex parte Crow Domestic dog was a United states Supreme Court appeal by an Indian who had been found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. The defendant was an American Indian who had been found guilty of the murder of another American Indian. Crow Dog argued that the commune courtroom did non have the jurisdiction to try him for a crime committed betwixt two American Indians that happened on an American Indian reservation. The court found that although the reservation was located within the territory covered by the district court'southward jurisdiction, Rev. Stat. § 2146 precluded the inmate'due south indictment in the district courtroom. Section 2146 stated that Rev. Stat. § 2145, which fabricated the criminal laws of the United States applicable to Indian country, did not apply to crimes committed by one Indian against some other, or to crimes for which an Indian was already punished past the law of his tribe. The Courtroom issued the writs of habeas corpus and certiorari to the Indian.[32]

Talton v. Mayes (1896) [edit]

The United states Supreme Court case of Talton five. Mayes was a conclusion respecting the authority of tribal governments. This case decided that the individual rights protections, specifically the Fifth Amendment, which limit federal, and later, state governments, practice not utilise to tribal government. Information technology reaffirmed earlier decisions, such as the 1831 Cherokee Nation 5. Georgia case, that gave Indian tribes the status of "domestic dependent nations", the sovereignty of which is independent of the federal government.[33] Talton v. Mayes is also a instance dealing with Native American dependence, equally it deliberated over and upheld the concept of congressional plenary say-so. This part of the decision led to some important pieces of legislation concerning Native Americans, the most important of which is the Indian Civil Rights Human action of 1968.

Good Shot v. United States (1900) [edit]

This United States Supreme Court case occurred when an American Indian shot and killed a non-Indian. The question arose of whether or not the United States Supreme Court had jurisdiction over this event. In an try to argue confronting the Supreme Courtroom having jurisdiction over the proceedings, the defendant filed a petition seeking a writ of certiorari. This request for judicial review, upon writ of error, was denied. The court held that a confidence for murder, punishable with expiry, was no less a conviction for a capital letter criminal offense by reason even taking into account the fact that the jury qualified the punishment. The American Indian defendant was sentenced to life in prison.[34]

Montoya v. United States (1901) [edit]

This The states Supreme court case came about when the surviving partner of the house of E. Montoya & Sons petitioned against the U.s.a. and the Mescalero Apache Indians for the value their livestock which was taken in March 1880. It was believed that the livestock was taken by "Victorio'southward Band" which was a group of these American Indians. It was argued that the group of American Indians who had taken the livestock were distinct from any other American Indian tribal group, and therefore the Mescalero Apache American Indian tribe should not be held responsible for what had occurred. After the hearing, the Supreme Court held that the judgment made previously in the Court of Claims would non exist changed. This is to say that the Mescalero Apache American Indian tribe would not be held answerable for the deportment of Victorio's Band. This effect demonstrates not simply the sovereignty of American Indian tribes from the United States, simply also their sovereignty from one some other. One group of American Indians cannot be held accountable for the deportment of another grouping of American Indians, even though they are all part of the American Indian nation.[35]

United states v. Winans (1905) [edit]

In this example, the Supreme Courtroom ruled in favor of the Yakama tribe, reaffirming their prerogative to fish and hunt on off-reservation land. Farther, the example established ii important principles regarding the interpretation of treaties. First, treaties would be interpreted in the way Indians would have understood them and "every bit justice and reason demand".[36] Second, the Reserved Rights Doctrine was established which states that treaties are non rights granted to the Indians, but rather "a reservation by the Indians of rights already possessed and not granted away by them".[37] These "reserved" rights, meaning never having been transferred to the United States or any other sovereign, include property rights, which include the rights to fish, chase and gather, and political rights. Political rights reserved to the Indian nations include the power to regulate domestic relations, revenue enhancement, administer justice, or practise civil and criminal jurisdiction.[38]

Winters v. United States (1908) [edit]

The United States Supreme Court case Winters five. The states was a case primarily dealing with h2o rights of American Indian reservations. This case clarified what h2o sources American Indian tribes had "implied" rights to put to use.[39] This case dealt with the Fort Belknap Indian Reservation and their correct to utilize the water source of the Milk River in Montana. The reservation had been created without clearly stating the explicit h2o rights that the Fort Belknap American Indian reservation had. This became a problem once non-Indian settlers began moving into the expanse and using the Milk River as a water source for their settlements.[40] As water sources are extremely thin and limited in Montana, this argument of who had the legal rights to apply the water was presented. After the case was tried, the Supreme Court came to the decision that the Fort Belknap reservation had reserved water rights through the 1888 understanding which had created the American Indian Reservation in the get-go identify. This example was very of import in setting a precedent for cases later the absorption era. Information technology was used as a precedent for the cases Arizona v. California, Tulee five. Washington, Washington v. McCoy, Nevada v. United states of america, Cappaert v. United States, Colorado River H2o Conservation Dist. five. United States, United States five. New Mexico, and Arizona v. San Carlos Apache Tribe of Arizona which all focused on the sovereignty of American Indian tribes.

Choate v. Trapp (1912) [edit]

Every bit more Native Americans received allotments through the Dawes Act, there was a great deal of public and state pressure to tax allottees. However, in the United States Supreme court case Choate five. Trapp, 224 U.S. 665 (1912), the court ruled for Indian allottees to exist exempt from land taxation.[29]

Clairmont v. The states (1912) [edit]

This U.s.a. Supreme Court case resulted when a defendant appealed the decision on his case. The defendant filed a writ of error to obtain review of his confidence later on being bedevilled of unlawfully introducing exhilarant liquor into an American Indian reservation. This act was found a violation of the Human activity of Congress of January 30, 1897, ch. 109, 29 Stat. 506. The defendant's appeal stated that the district court lacked jurisdiction because the criminal offense for which he was convicted did non occur in American Indian state. The accused had been arrested while traveling on a train that had but crossed over from American Indian country. The defendant'south argument held and the Supreme Court reversed the defendant'south conviction remanding the crusade to the district court with directions to quash the indictment and discharge the defendant.[41]

U.s.a. v. Quiver (1916) [edit]

This instance was sent to the United States Supreme Court after first appearing in a commune courtroom in Due south Dakota. The case dealt with adultery committed on a Sioux Indian reservation. The district court had held that adultery committed by an Indian with another Indian on an Indian reservation was not punishable nether the act of March three, 1887, c. 397, 24 Stat. 635, at present § 316 of the Penal Code. This decision was made because the criminal offense occurred on a Sioux Indian reservation which is not said to be under jurisdiction of the district courtroom. The United States Supreme Courtroom affirmed the judgment of the commune court saying that the adultery was not punishable every bit it had occurred between two American Indians on an American Indian reservation.[42]

Native American education and boarding schools [edit]

Non-reservation boarding schools [edit]

In 1634, Fr. Andrew White of the Jesuits established a mission in what is now the state of Maryland, and the purpose of the mission, stated through an interpreter to the chief of an Indian tribe there, was "to extend civilisation and pedagogy to his ignorant race, and testify them the fashion to heaven".[43] The mission's annual records written report that by 1640, a community had been founded which they named St. Mary'southward, and the Indians were sending their children there to be educated.[44] This included the daughter of the Pascatoe Indian master Tayac, which suggests not only a school for Indians, but either a school for girls, or an early on co-ed school. The same records report that in 1677, "a school for humanities was opened by our Society in the centre of [Maryland], directed past 2 of the Fathers; and the native youth, applying themselves assiduously to study, fabricated good progress. Maryland and the recently established school sent two boys to St. Omer who yielded in abilities to few Europeans, when competing for the laurels of being commencement in their grade. So that non aureate, nor silver, nor the other products of the earth lonely, but men also are gathered from thence to bring those regions, which foreigners have unjustly called ferocious, to a higher land of virtue and cultivation."[45]

In 1727, the Sisters of the Lodge of Saint Ursula founded Ursuline Academy in New Orleans, which is currently the oldest, continuously-operating school for girls and the oldest Catholic schoolhouse in the United States. From the fourth dimension of its foundation information technology offered the first classes for Native American girls, and would later on offering classes for female African-American slaves and free women of color.

Male Carlisle Schoolhouse students (1879)

The Carlisle Indian Industrial School founded by Richard Henry Pratt in 1879 was the start Indian boarding school established. Pratt was encouraged by the progress of Native Americans whom he had supervised as prisoners in Florida, where they had received basic education. When released, several were sponsored by American church groups to attend institutions such as Hampton Institute. He believed education was the ways to bring American Indians into society.

Pratt professed "absorption through full immersion". Because he had seen men educated at schools like Hampton Institute get educated and alloyed, he believed the principles could exist extended to Indian children. Immersing them in the larger culture would help them suit. In addition to reading, writing, and arithmetic, the Carlisle curriculum was modeled on the many industrial schools: it constituted vocational training for boys and domestic scientific discipline for girls, in expectation of their opportunities on the reservations, including chores around the school and producing goods for marketplace. In the summer, students were assigned to local farms and townspeople for boarding and to go on their immersion. They also provided labor at low price, at a fourth dimension when many children earned pay for their families.

Carlisle and its curriculum became the model for schools sponsored by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. By 1902 at that place were twenty-v federally funded non-reservation schools across fifteen states and territories with a total enrollment of over 6,000. Although federal legislation fabricated teaching compulsory for Native Americans, removing students from reservations required parental authorization. Officials coerced parents into releasing a quota of students from any given reservation.

Pupils at Carlisle Indian Industrial Schoolhouse, Pennsylvania (c. 1900)

In one case the new students arrived at the boarding schools, their lives altered drastically. They were usually given new haircuts, uniforms of European-American fashion clothes, and even new English language names, sometimes based on their own, other times assigned at random. They could no longer speak their own languages, even with each other. They were expected to attend Christian churches. Their lives were run by the strict orders of their teachers, and information technology often included grueling chores and stiff punishments.

Additionally, infectious disease was widespread in society, and often swept through the schools. This was due to lack of information about causes and prevention, inadequate sanitation, insufficient funding for meals, overcrowded conditions, and students whose resistance was low.

Native American group of Carlisle Indian Industrial Schoolhouse male and female person students; brick dormitories and bandstand in background (1879)

An Indian boarding school was one of many schools that were established in the United States during the late 19th century to brainwash Native American youths co-ordinate to American standards. In some areas, these schools were primarily run past missionaries. Especially given the young age of some of the children sent to the schools, they accept been documented as traumatic experiences for many of the children who attended them. They were by and large forbidden to speak their native languages, taught Christianity instead of their native religions, and in numerous other ways forced to carelessness their Indian identity and prefer American culture. Many cases of mental and sexual abuse have been documented, as in Northward Dakota.[ citation needed ]

Piffling recognition to the drastic change in life of the younger children was evident in the forced federal rulings for compulsory schooling and sometimes harsh estimation in methods of gathering, even to intruding in the Indian homes. This proved extremely stressful to those who lived in the remote desert of Arizona on the Hopi Mesas well isolated from the American civilization. Separation and boarding school living would last several years.

Forced collection of Oraibi children and preparing for a ii twenty-four hour period drive to the government school at Keams Canyon

Information technology remains today, a topic in traditional Hopi Indian recitations of their history—the traumatic situation and resistance to government edicts for forced schooling. Conservatives in the village of Oraibi opposed sending their young children to the Government schoolhouse located in Keams Coulee. It was far enough away to require full time boarding for at least each school year. At the closing of the nineteenth century, the Hopi were for the most part a walking club. Unfortunately, visits between family and the schooled children were impossible. As a result, children were hidden to prevent forced collection by the U.S. war machine. Wisely, the Indian Agent, Leo Crane [46] requested the military machine troop to remain in the background while he and his helpers searched and gathered the youngsters for their multi-day travel by armed forces wagon and yr-long separation from their family.[47]

By 1923 in the Northwest, most Indian schools had airtight and Indian students were attending public schools. States took on increasing responsibility for their education.[48] Other studies suggest attendance in some Indian boarding schools grew in areas of the U.s.a. throughout the first one-half of the 20th century, doubling from 1900 to the 1960s.[49] Enrollment reached its highest point in the 1970s. In 1973, 60,000 American Indian children were estimated to have been enrolled in an Indian boarding schoolhouse.[50] [51] In 1976, the Tobeluk vs Lund case was brought by teenage Native Alaskan plaintiffs confronting the Country of Alaska alleging that the public schoolhouse state of affairs was still an unequal one.

The Meriam Study of 1928 [edit]

The Meriam Report,[52] officially titled "The Problem of Indian Administration", was prepared for the Section of Interior. Assessments found the schools to be underfunded and understaffed, too heavily institutionalized, and run too rigidly. What had started every bit an idealistic program near education had gotten subverted.

It recommended:

- abolishing the "Uniform Course of Written report", which taught only majority American cultural values;

- having younger children attend community schools almost home, though older children should exist able to attend not-reservation schools; and

- ensuring that the Indian Service provided Native Americans with the skills and education to adapt both in their own traditional communities (which tended to be more rural) and the larger American society.

Indian New Deal [edit]

John Collier, the Commissioner of Indian Diplomacy, 1933–1945, fix the priorities of the New Deal policies toward Native Americans, with an emphasis on reversing as much of the assimilationist policy as he could. Collier was instrumental in ending the loss of reservations lands held by Indians, and in enabling many tribal nations to re-establish cocky-regime and preserve their traditional culture. Some Indian tribes rejected the unwarranted outside interference with their own political systems the new approach had brought them.

Collier's 1920– 1922 visit to Taos Pueblo had a lasting impression on Collier. He now saw the Indian world as morally superior to American society, which he considered to be "physically, religiously, socially, and aesthetically shattered, dismembered, directionless".[53] Collier came nether assault for his romantic views about the moral superiority of traditional society equally opposed to modernity.[54] Philp says later on his experience at the Taos Pueblo, Collier "made a lifelong delivery to preserve tribal community life considering it offered a cultural alternative to modernity. ... His romantic stereotyping of Indians often did not fit the reality of contemporary tribal life."[55]

Collier carried through the Indian New Deal with Congress' passage of the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Information technology was one of the nearly influential and lasting pieces of legislation relating to federal Indian policy. Too known equally the Wheeler–Howard Act, this legislation reversed fifty years of assimilation policies by emphasizing Indian self-decision and a render of communal Indian state, which was in straight contrast with the objectives of the Indian General Allotment Act of 1887.

Collier was also responsible for getting the Johnson–O'Malley Act passed in 1934, which immune the Secretarial assistant of the Interior to sign contracts with country governments to subsidize public schooling, medical care, and other services for Indians who did not live on reservations. The act was effective only in Minnesota.[56]

Collier'south support of the Navajo Livestock Reduction program resulted in Navajo opposition to the Indian New Deal.[57] [58] The Indian Rights Association denounced Collier as a "dictator" and accused him of a "near reign of terror" on the Navajo reservation.[59] According to historian Brian Dippie, "(Collier) became an object of 'burning hatred' among the very people whose bug so preoccupied him."[59]

[edit]

Several events in the late 1960s and mid-1970s (Kennedy Study, National Study of American Indian Education, Indian Cocky-Determination and Education Assist Human activity of 1975) led to renewed emphasis on community schools. Many big Indian boarding schools closed in the 1980s and early 1990s. In 2007, nine,500 American Indian children lived in an Indian boarding schoolhouse dormitory.[ commendation needed ] From 1879 when the Carlisle Indian Schoolhouse was founded to the nowadays 24-hour interval, more than than 100,000 American Indians are estimated to have attended an Indian boarding school.

A similar system in Canada was known as the Canadian residential school arrangement.[sixty]

Lasting furnishings of the Americanization policy [edit]

While the concerted effort to assimilate Native Americans into American culture was abased officially, integration of Native American tribes and individuals continues to the present twenty-four hours. Often Native Americans are perceived equally having been alloyed. Even so, some Native Americans feel a particular sense of being from another social club or do not belong in a primarily "white" European majority order, despite efforts to socially integrate them.[ citation needed ]

In the mid-20th century, as efforts were all the same under style for absorption, some studies treated American Indians simply every bit some other ethnic minority, rather than citizens of semi-sovereign entities which they are entitled to past treaty. The following quote from the May 1957 result of Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Scientific discipline, shows this:

The place of Indians in American society may be seen as 1 attribute of the question of the integration of minority groups into the social arrangement.[61]

Since the 1960s, however, in that location have been major changes in society. Included is a broader appreciation for the pluralistic nature of United States club and its many ethnic groups, as well equally for the special status of Native American nations. More than recent legislation to protect Native American religious practices, for instance, points to major changes in regime policy. Similarly the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Deed of 1990 was another recognition of the special nature of Native American culture and federal responsibleness to protect it.

Every bit of 2013, "Montana is the only country in the U.S. with a constitutional mandate to teach American Indian history, culture, and heritage to preschool through higher instruction students via the Indian Pedagogy for All Act."[62] The "Indian Education for All" curriculum, created by the Montana Office of Public Instruction, is distributed online for primary and secondary schools.[63]

Mod cultural and linguistic preservation [edit]

To evade a shift to English, some Native American tribes have initiated language immersion schools for children, where a native Indian language is the medium of didactics. For case, the Cherokee Nation instigated a ten-year language preservation plan that involved growing new fluent speakers of the Cherokee linguistic communication from babyhood on up through school immersion programs besides equally a collaborative community effort to continue to use the language at abode.[64] This plan was function of an ambitious goal that in 50 years, 80% or more than of the Cherokee people will exist fluent in the linguistic communication.[65] The Cherokee Preservation Foundation has invested $3 million into opening schools, grooming teachers, and developing curricula for language teaching, as well as initiating customs gatherings where the language can be actively used.[65] Formed in 2006, the Kituwah Preservation & Teaching Program (KPEP) on the Qualla Boundary focuses on language immersion programs for children from nascence to 5th grade, developing cultural resources for the general public and community linguistic communication programs to foster the Cherokee language among adults.[66]

At that place is also a Cherokee linguistic communication immersion schoolhouse in Tahlequah, Oklahoma that educates students from pre-school through eighth course.[67] Considering Oklahoma's official language is English, Cherokee immersion students are hindered when taking state-mandated tests because they have little competence in English.[68] The Section of Teaching of Oklahoma said that in 2012 state tests: xi% of the school's sixth-graders showed proficiency in math, and 25% showed proficiency in reading; 31% of the seventh-graders showed proficiency in math, and 87% showed proficiency in reading; 50% of the eighth-graders showed proficiency in math, and 78% showed proficiency in reading.[68] The Oklahoma Department of Pedagogy listed the charter school every bit a Targeted Intervention school, meaning the schoolhouse was identified as a low-performing school but has not and then that information technology was a Priority School.[68] Ultimately, the school made a C, or a 2.33 grade signal average on the land's A–F report card organization.[68] The report card shows the schoolhouse getting an F in mathematics achievement and mathematics growth, a C in social studies accomplishment, a D in reading achievement, and an A in reading growth and student omnipresence.[68] "The C we made is tremendous," said schoolhouse primary Holly Davis, "[t]here is no English instruction in our school's younger grades, and we gave them this test in English."[68] She said she had anticipated the low course because it was the schoolhouse's first yr as a state-funded lease school, and many students had difficulty with English.[68] Eighth graders who graduate from the Tahlequah immersion school are fluent speakers of the language, and they usually keep to nourish Sequoyah High School where classes are taught in both English and Cherokee.

See also [edit]

- Acculturation

- American Indian boarding schools

- Bureau of Indian Affairs

- Canadian Indian residential school organisation

- Contemporary Native American issues in the U.s.

- Cultural appropriation

- European colonization of the Americas

- Gradual Civilization Deed

- Indian Relocation Act of 1956

- Indian Placement Program

- Indian removal

- Indian termination policy

- Mod social statistics of Native Americans

- Native American identity in the United States

- Native American reservation politics

- Native American cocky-decision

- Native Americans and reservation inequality

- Russification

- St. Joseph's Indian School

- Tribal disenrollment

- Our Fires Still Burn

- American Indian outing programs

Footnotes [edit]

- ^ Frederick Hoxie, (1984). A Last Promise: The Entrada to Digest the Indians, 1880–1920. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- ^ a b c lon, Peter. ""The Reform Begins"". Beak Nye the Scientific discipline Guy. p. 201. ISBN 0-9650631-0-7.

- ^ a b Perdue, Theda (2003). "Affiliate 2 "Both White and Red"". Mixed Claret Indians: Racial Structure in the Early Southward. The Academy of Georgia Press. p. 51. ISBN0-8203-2731-X.

- ^ Gary Warrick, "European Infectious Illness and Depopulation of the Wendat-Tionontate (Huron-Petun)", Globe Archaeology 35 (October 2003), 258–275.

- ^ a b Breen, T. H. (2010). American Insurgents, American Patriots: The Revolution of the People . New York: Hill and Wang. ISBN9780809075881.

- ^ a b c Fritz, Henry E. (1963). The Motion for Indian in 1860–1890. University of Pennsylvania Printing.

- ^ a b Miller, Eric (1994). "Washington and the Northwest War, Part One". George Washington And Indians. Eric Miller. Retrieved 2008-05-02 .

- ^ Remini, Robert. ""Brothers, Listen ... You Must Submit"". Andrew Jackson. History Book Club. p. 258. ISBN 0-9650631-0-7.

- ^ Hoxie, Frederick (1984). A Last Hope: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880–1920. Lincoln: Academy of Nebraska Printing.

- ^ Robert H. Keller, American Protestantism and United States Indian Policy, 1869-82 (1983)

- ^ "State of the Marriage Address: Ulysses Due south. Grant (December 4, 1871)".

- ^ Cary C. Collins, "A Fall From Grace: Sectarianism and the Grant Peace Policy in Western Washington Territory, 1869–1882", Pacific Northwest Forum (1995) 8#ii pp 55–77

- ^ Joseph Due east. Illick, "'Some Of Our All-time Friends Are Indians...': Quaker Attitudes and Actions Regarding the Western Indians during the Grant Assistants", Western Historical Quarterly (1971) 2#3 pp. 283–294 in JSTOR

- ^ Robert A. Trennert, "John H. Stout and the Grant Peace Policy amid the Pimas", Arizona & the West (1986) 28#1 pp. 45–68

- ^ Norman Bender, New Promise for the Indians: The Grant Peace Policy and the Navajos in the 1870s (1989)

- ^ "Oklahoma Statehood, Nov xvi, 1907". 15 August 2016.

- ^ Brian West. Dippie, "'What Will Congress Practice Virtually It?' The Congressional Reaction to the Little Big Horn Disaster", Northward Dakota History (1970) 37#3 pp. 161–189

- ^ http://rcliton.files.wordpress.com/2007/11/code-of-indian-offenses.pdf, accessed 27 May 2011

- ^ http://tribal-law.blogspot.com/2008/02/lawmaking-of-indian-offenses.html, accessed 27 May 2011

- ^ Written report of the Secretary of the Interior, Volume II. Washington: GPO, 189, pp. lxxxiii-lxxxix.

- ^ a b c Frederick e. Hoxie (2007). "What was Taney thinking? American Indian Citizenship in the era of Dred Scott" (PDF). Chicago-Kent Law Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on September fifteen, 2007. Retrieved 2013-11-04 .

- ^ Hoxie, Frederick E. Talking Back to Civilization: Indian Voices from the Progressive Era. New York: St. Martin's. 2001. (178) Print.

- ^ a b c Tomlins, Christopher 50. The Us Supreme Courtroom: the pursuit of justice. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. 2005. (175–176) Print.

- ^ a b Wilkins, David Due east. American Indian Sovereignty and the U.S. Supreme Court: The Masking of Justice. University of Texas Press, 1997. (78–81) Print.

- ^ Tomlins, Christopher 50. The The states Supreme Courtroom: the pursuit of justice. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. 2005. (191) Print.

- ^ "FindLaw's United States Supreme Court case and opinions".

- ^ Duthu, Bruce. American Indians and the Law. New York: Penguin Books, 2008. (XXV) Impress.

- ^ "U.s.a. v. Kagama, 118 U.Southward. 375 (1886)". Findlaw. Retrieved on 2009-ten-xix.

- ^ a b Wilkins, David, and K. Tsianina Lomawaima. Uneven Footing: American Indian Sovereignty and Federal Constabulary. University of Oklahoma Press, 2001. (151) Print.

- ^ Canby Jr., William. American Indian Law In a Nut Shell, quaternary edition. West Group, 2004. (1) Print.

- ^ Ruby-red Man's Land White Human being's Land second edition, Wilcomb B. Washburn, 1995, p. 141

- ^ Ex parte Crow Dog, 109 U.S. 556 (1883)

- ^ "Total text stance from Justia.com"

- ^ "Practiced Shot v. United States. LexisNexis. 15 October 2009.

- ^ "Montoya v. United States". LexisNexis. 15 October 2009.

- ^ Washington v. Washington Country Commercial Passenger Fishing Vessel Association, 443 U.Southward. 658, 668

- ^ Shultz, Jeffrey D. (2000). Encyclopedia of Minorities in American Politics, p. 710. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 1-57356-149-5

- ^ Wilkins, David E. and Lomawaima, K. Tsianina (2002). Uneven Ground: American Indian Sovereignty and Federal Law, p. 125. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3395-9

- ^ Duthu, N. (2008). "American Indians and the Law", p. 105. Penguin Group Inc., New York. ISBN 978-0-670-01857-4.

- ^ Shurts, John (2000). "Indian Reserved Water Rights", p. 15. University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806132108

- ^ "Clairmont v. United states". LexisNexis. xv October 2009.

- ^ "United States 5. Quiver". LexisNexis. fifteen October 2009.

- ^ Foley, Henry. Records of the English language Province of the Society of Jesus. 1875. London: Burns and Oates. p. 352.

- ^ Foley, Henry. Records of the English Province of the Social club of Jesus. 1875. London: Burns and Oates. p. 379

- ^ Foley, Henry. Records of the English Province of the Gild of Jesus. 1875. London: Burns and Oates. p. 394

- ^ Crane, Leo. Indians of the Enchanted Desert. Boston, MA. Little, Brown, and Co. 1925

- ^ Pecina, Ron and Pecina, Bob; Fine art by Neil David. Neil David's Hopi World. pp80-84. Schiffer Publishing Ltd., 2011. ISBN 978-0-7643-3808-3.

- ^ Carolyn Marr, "Assimilation through Education: Indian Boarding Schools in the Northwest", University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

- ^ Colmant, S.A. (2000). "U.S. and Canadian Boarding Schools: A Review, Past and Present", Native Americas Periodical,17 (4), 24–30.

- ^ Colmant, S.A. (2000). "U.South. and Canadian Boarding Schools: A Review, By and Nowadays", Native Americas Periodical, 17 (4), 24–30

- ^ C. Hammerschlag; C.P. Alderfer; and D. Berg, (1973). "Indian Didactics: A Man Systems Analysis", American Journal of Psychiatry

- ^ "Alaskool - 1928 Report on "Trouble of Indian Administration"".

- ^ John Collier, "Does the Government Welcome the Indian Arts?" The American Magazine of Art. Anniversary Supplement vol. 27, no. 9, Office two (1934): 10–xiii

- ^ Stephen J. Kunitz, "The social philosophy of John Collier." Ethnohistory (1971): 213–229. in JSTOR

- ^ Kenneth R. Philp. "Collier, John". American National Biography Online, February 2000. Accessed May 5, 2015.

- ^ James Stuart Olson; Raymond Wilson (1986). Native Americans in the Twentieth Century. Academy of Illinois Press. pp. 113–15. ISBN9780252012853.

- ^ Peter Iverson, &f=false Diné: A History of the Navajos (2002) p 144

- ^ Donald A. Grinde Jr, "Navajo Opposition to the Indian New Deal." Integrated Education (1981) 19#3-6 pp: 79–87.

- ^ a b Brian West. Dippie, The Vanishing American: White Attitudes and U.South. Indian Policy (1991) pp 333–336, quote p 335

- ^ Andrea Smith, "Soul Wound: The Legacy of Native American Schools" Archived 2006-02-08 at the Wayback Car, Amnesty Magazine, Amnesty International website

- ^ Dozier, Edward, et al. "The Integration of Americans of Indian Descent", Register of the American Academy of Political and Social Scientific discipline, Vol. 311, American Indians and American Life May 1957, pp. 158–165.

- ^ "Native American Eye Facts". The University of Montana. Archived from the original on 2013-10-29. Retrieved 2013-ten-27 .

- ^ "Indian Pedagogy for All Lesson Plans". Archived from the original on 2013-10-28. Retrieved 2013-x-27 .

- ^ "Native Now : Linguistic communication: Cherokee". We Shall Remain - American Experience - PBS. 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2014.

- ^ a b "Cherokee Linguistic communication Revitalization". Cherokee Preservation Foundation. 2014. Archived from the original on April 7, 2014. Retrieved Apr ix, 2014.

- ^ Kituwah Preservation & Education Plan Powerpoint, past Renissa Walker (2012)'. 2012. Impress.

- ^ Chavez, Will (April v, 2012). "Immersion students win trophies at language fair". Cherokeephoenix.org . Retrieved April 8, 2013.

- ^ a b c d eastward f g "Cherokee Immersion School Strives to Save Tribal Language". Youth on Race. Archived from the original on July 3, 2014. Retrieved June five, 2014.

Farther reading [edit]

- Adams, David Wallace (1995). Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School Experience, 1875–1928. University Printing of Kansas.

- Ahern, Wilbert H. (1994). "An Experiment Aborted: Returned Indian Students in the Indian School Service, 1881–1908", Ethnohistory 44(2), 246–267.

- Borhek, J. T. (1995). "Ethnic Group Cohesion", American Periodical of Sociology 9(twoscore), one–16.

- Ellis, Clyde (1996). To Modify Them Forever: Indian Teaching at the Rainy Mountain Boarding School, 1893–1920. Norman: Academy of Oklahoma Press.

- Hill, Howard C. (1919). "The Americanization Movement", American Journal of Sociology, 24 (6), 609–642.

- Hoxie, Frederick (1984). A Terminal Promise: The Campaign to Assimilate the Indians, 1880–1920. Lincoln: Academy of Nebraska Printing.

- McKenzie, Fayette Avery (1914). "The Assimilation of the American Indian", The American Journal of Sociology, Vol. nineteen, No. half dozen. (May), pp. 761–772.

- Peshkin, Alan (1997). Places of Memory: Whiteman's Schools and Native American Communities. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Rahill, Peter J. The Catholic Indian Missions and Grant's Peace Policy 1870-1884 (1953) online

- Senier, Siobhan. Voices of American Indian Assimilation and Resistance: Helen Hunt Jackson, Sarah Winnemucca, and Victoria Howard. University of Oklahoma Press (2003).

- Spring, Joel (1994). Deculturalization and the Struggle for Equality: A Brief History of the Didactics of Dominated Cultures in the United states of america. McGraw-Loma Inc.

- Steger, Manfred B (2003). Globalization: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Tatum, Laurie. Our Red Brothers and the Peace Policy of President Ulysses Due south. Grant. University of Nebraska Press (1970).

- Wright, Robin 1000. (1991). A Fourth dimension of Gathering: Native Heritage in Washington State. Academy of Washington Printing and the Thomas Shush Memorial Washington Land Museum.

External links [edit]

- Bureau of Indian Affairs, United states Department of The Interior

- "History of Native Americans in the U.S.", Hartford World History Archives

- NPR Report, National Public Radio

What Method Of Assimilation Did Settlers Use To Target Native American Youths?,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cultural_assimilation_of_Native_Americans

Posted by: sosaammed1971.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Method Of Assimilation Did Settlers Use To Target Native American Youths?"

Post a Comment